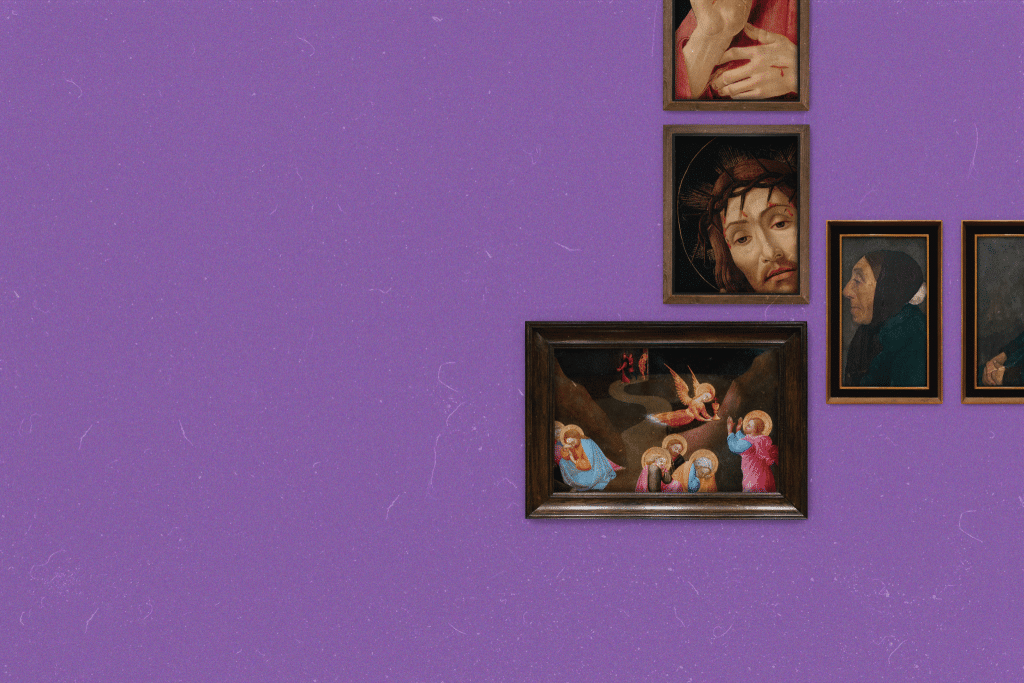

Marble hallways lead past ancient artwork. Here is a Latin Bible from the 1200s with a gold leaf illustration of David fighting Goliath. A glistening fish mosaic fashioned by a Christian believer during the time of the Roman persecutions. A stone altar upon which Mass was celebrated over 1,300 years ago.

The hallways continue. Reliquaries, bronze incense censers, saints chiseled from stone. Here is an intimate, nose-to-nose encounter with the brutalized but gentle face of the resurrected Christ by the master Renaissance painter, Botticelli. Another masterwork, the “Immaculate Conception,” hangs high on a granite wall.

This colossal painting by the Spaniard Murillo depicts the Holy Virgin lifted up by infant angels. She folds her delicate hands and looks skyward. We have seen this image so many times on prayer cards and church calendars. But here it is — really.

Where are all of these priceless works of art? Are we in an ancient basilica in Rome? A medieval cathedral in France? Are we at the Louvre in Paris or the Prado in Madrid?

Nope, this is Detroit, Michigan. We are in the A. Alfred Taubman wing of the Detroit Institute of the Arts, right on Woodward Avenue. The Taubman wing, with its multiple galleries, each one more stunning than the next, exhibits hundreds of precious Christian artworks and artifacts spanning fourteen centuries of European history.

A visit to the DIA could satisfy anyone’s general interest in art history. But for Catholics, a visit could also become a moving spiritual journey through the practice of visio divina: reflecting upon — praying with — these great works of beauty and faith.

Praying with the Eyes

Readers may be familiar with lectio divina, or praying with Sacred Scripture. But how does one practice visio divina, meaning “sacred seeing” or praying with the eyes?

There are plenty of books and online articles on this method. (Check out this article by Father J.J. Mech, art aficionado and rector of Sacred Heart Cathedral) To give you a quick sense of visio divina, here is a composite summary:

First of all, turn the journey over. Ask the Spirit to lead you to images he would like you to choose.

Quiet yourself before the image, perhaps closing your eyes. Deep breathing might help to clear the mind and relax the body.

Then open your eyes. Let them rest on the image. Even place yourself into the image’s scene. Why do you think God has drawn you here?

Begin to articulate the unspoken feelings the image has awakened. What prayer do you feel moved to offer? Allow God to speak to the inner self.

Finally, return to a calming silence. Thank the Spirit for guidance.

“The visual arts can offer some of the richest and most satisfying prayer experiences by engaging more of our senses,” explains Father Mech, who often uses sacred images in his prayer life. “Visio divina invites us to be seen, addressed, surprised and transformed by God.”

Father Mech also recommends “stretching yourself”: consider praying with an art object that is abstract or from another culture.

Encountering Beauty

Father Paul Snyder has brought his great love for art with him into his priestly ministry. Before he entered the seminary, Father Snyder worked for the auto industry in design and studied art history in college. As pastor of St. Mary Parish in Royal Oak, he leads pilgrimages to the Detroit Institute of the Arts focused on the visio divina meditation approach.

“The Church has looked to beauty to help us evangelize for centuries,” Father says. “Some of the most famous artworks in the world were commissioned by the Church to glorify God.

“So, helping people to encounter God through beauty is something I have enjoyed for a long time.”

Around 30 or so parishioners and non-parishioners join him on a typical pilgrimage. They come together in the museum lobby for a prayer and a short explanation of visio divina. Next the pilgrims fan out to seek a sacred image or art object that intrigues them.

“I encourage them to take time to ‘read’ the artwork like they would meditate on a passage of Scripture,” Father Snyder says. “What stands out? Is it the light or shadows? The colors? Is it the subject?”

After about 45 minutes, the seekers return to share insights.

A spiritual journey to a non-sacred place like the DIA is a “shallow entry point,” explains Father Snyder, meaning a more relaxed way to learn about the Catholic Faith. “You don’t have to be an expert on art or theology to appreciate beauty.”

Tool for Prayer

St. Mary parishioner Erin Cvengros has joined Father Snyder on two DIA excursions. She sees the pilgrimages as support for her ongoing conversion that began as a college student.

Erin found herself attracted to an image of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane, by the early Renaissance painter Sassetta. While pondering the figure of an attending angel presenting a cup of suffering to the Lord, she received a nudge of intuition.

“As I was praying, I was suddenly reminded of the Annunciation — the comparison of this angel with the angel that appeared to Mary. It struck me that both Mary and Jesus had similar responses, ‘Thy will be done.’”

Considering his background in the arts, as a classical music composer and choral tenor, Patrick Braga naturally felt drawn to join one of Father Snyder’s pilgrimages. The St. Mary parishioner is a former agnostic who now embraces the Catholic understanding that “art is not an end unto itself but as a means to glorify God.”

What art object attracted Patrick’s attention and became what he calls a “tool for prayer”? It was the figurines carved from ivory that illustrate events in Christ’s life, fashioned by unknown medieval artists.

“What struck me was their playfulness. How they capture the humanity of the people who produced them.

“The continuity of Catholics through the ages is so fascinating,” Patrick continues. “Catholics trying to develop a relationship with Christ and finding their own mode of expression. Their continuity with us today.”

As for Father Snyder, a favorite DIA piece is “The Annunciation” by Fra (Friar) Angelico, “the Angelic Painter.” The Italian Dominican paints the Archangel Gabriel and the young Virgin with glittering gold leaf to signify the sacredness of their meeting.

Father Snyder says he looks forward to leading future pilgrimages. Erin and Patrick say they would definitely go again, and both intend to return to the DIA to practice the art of “sacred seeing” on their own.

Time Travel

On one of my own trips to the DIA in January, I took the Grand Tour, a walking introduction to the DIA’s three floors of galleries. Here are the discoveries that pulled me in for a deeper look.

“Old Peasant Woman,” ca. 1905, German, Paula Modersohn-Becker

The woman’s homely but dignified profile suggests her acceptance of her soon-to-be-completed circle of life. Do the tiny fresh flowers splayed on her lap symbolize her childhood? She folds her oversized hands with a delicacy that evokes the hands of Murillo’s “Immaculate Conception.” I learned the DIA has the best collection of German Expressionism paintings outside of Europe. Many of these images, including this one, were rescued from the Nazis as they purged Germany of so-called “degenerative” art.

“Chapel from the Chateau de Lannoy,” ca. 1522, French Gothic.

The DIA purchased the family worship space fully intact. The limestone walls, vaulted ceiling and stained glass have been reconstructed piece-by-piece in the medieval gallery. Step into this time portal and marvel at the period devotional pieces, such a brilliant triptych (meaning a three-paneled work) from the 1300s. I asked a program interpreter if she has ever noticed anyone praying in the chapel. “Sure, all of the time!”

“The Lonely Pine,” 1893, American, George Inness.

The scene seems forlorn at first. A single pine tree stands in a field of muted green. A storm cloud crosses a horizon of dull orange. All is suppressed impression, like looking through “a glass darkly.” Yet, the painting attracts. Have you ever walked alone along a Lake Michigan shore in a cooling breeze as the sunset burns the sky? Alone. . . but not forlorn, but feeling truly alive? Inness captures this feeling precisely. For Inness, there is a Life-Force shimmering beneath the surface of even the loneliest places.

Beauty in All

Found throughout the DIA, beyond the Taubman’s “Catholic” galleries, are powerful images that bespeak of the Spirit in all. The massive wilderness landscapes of the Dutch Golden Age signify God’s fascinating yet terrifying creative power. The Asian, African, Islamic and Native American art objects on the first floor, through their beauty and craftsmanship, reflect the beauty and unity of the One. (St. John Paul II calls this mystical relationship “the language of beauty.”

Do not miss the mother-daughter works in the African American hall. Alison Saar chainsaws a full-sized female body from the trunk of a tree and encases it in oxidized copper. Hands hide her face; dark droplets weep from the skin. To be human is sometimes travail. (“Blood/Sweat/Tears,” 2005.)

Alison’s mother, Betye Saar, pieces together found materials to create a rough picture frame. At the frame’s center is a small painting of an elderly black woman — a Caribbean ritual healer. With Miraculous Medals at its corners, the work “Beyond Midnight” (2002) clearly evokes a Russian icon; the woman a cultural saint.

Without a doubt, as you wander the halls on your pilgrimage, allowing the Spirit to lead you, your own favorites will emerge from the walls and exhibits like surprising visions.

Can’t make it to the DIA? Download from its website thousands of works from over 100 galleries and practice praying with Catholic eyes at home.