There are a million ways to be an American and a million ways to be a Saint. And while there are still only 14 canonized Americans, there are plenty of folks from the United States who are on their way to canonization. This Independence Day, sit with some of our American Saints-to-be and ask the Lord what holiness looks like for you.

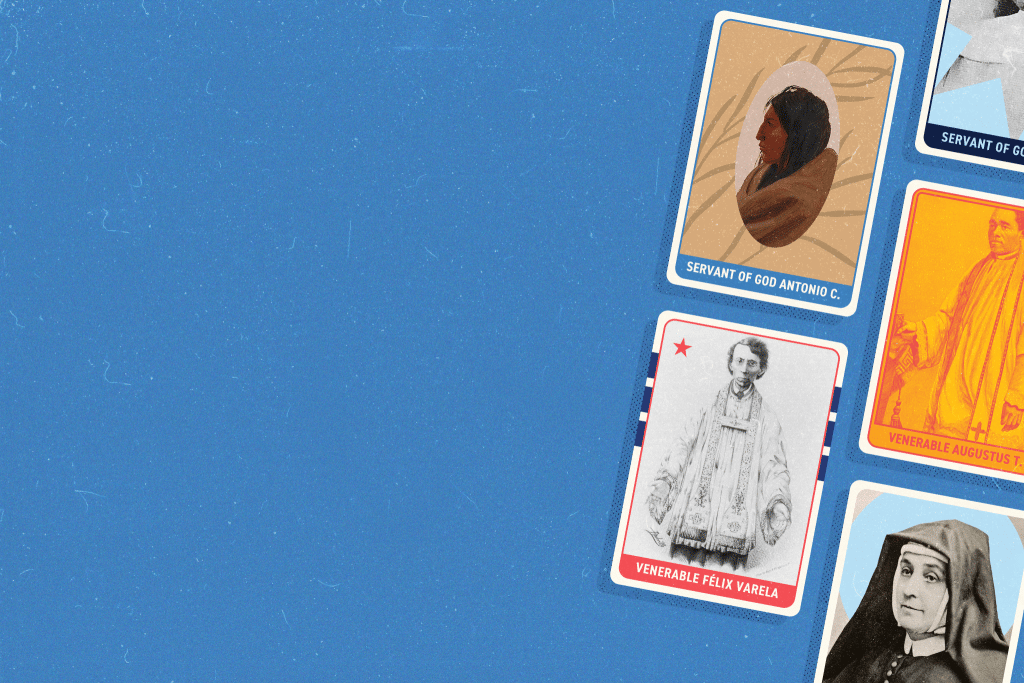

Servant of God Antonio Cuipa (d. 1704) was the son of a Christian Apalachee chief in present-day Florida; educated by Franciscan missionaries, Antonio went on to become a leader in his community, second-in-command over the thousands of Native Christians associated with his mission. He was a husband and father of two, a hard-working carpenter, a flutist and an evangelist. Though he often accompanied the missionaries as they evangelized local people, Antonio also left them behind at times, knowing the antipathy many Native Americans had toward men who looked like those who had attacked and enslaved them. Antonio and his Native friends would approach nearby communities, whereupon Antonio would play his flute. When the people were suitably impressed, he would offer them wooden flutes he had carved himself. Only then would he begin to preach the Gospel, starting at places of commonality between Christians and those who followed traditional Native spiritual practices. Antonio was ultimately martyred, during which suffering he experienced the first recorded Marian apparition in what’s now the United States.

Venerable Felix Varela y Morales (1788-1853) was a Cuban priest and statesman, a seminary professor whose intellectual contributions to Cuba were so significant that he’s often called, “the one who taught us how to think.” When he was sent as a representative to the Spanish Parliament, Father Varela took the opportunity to speak out in favor of the abolition of slavery and the freedom of Spanish colonies, though he knew such abolitionist sentiment would likely mean execution as a traitor. He received a death sentence for his trouble but escaped to New York. There he spent decades in exile, serving immigrant communities (particularly the Irish), starting the first Spanish-language newspaper in the United States, and working to form the Catholic Church in America to lead the way in support of immigrants.

Venerable Augustus Tolton (1854-1897) was the first African American Catholic priest to acknowledge his African heritage publicly. Born into slavery in Missouri, Tolton and his family escaped to Illinois where he discerned a call to the priesthood despite the racism he endured from white Catholics. But while his pastor supported his vocation, Tolton was rejected by every American seminary because of his race. Finally, he was accepted at a seminary in Rome and prepared to serve in the African missions as the American bishops were quite sure that the American Church wasn’t ready for Black priests. But Rome saw differently, and Father Tolton was sent first to Quincy, Illinois, and then to Chicago where, despite constant struggles with prejudiced clergy and laity, he served his people tirelessly, dying of exhaustion at only 43.

Venerable Cornelia Connelly (1809-1879) was born to a Protestant family in Pennsylvania and was married to an Episcopal priest when the two decided to convert to Catholicism. Not long after the couple’s infant daughter and toddler son died, Cornelia’s husband Pierce moved the family to Europe and announced that he would be separating from his pregnant wife to pursue ordination. Feeling she had no choice, Cornelia took a vow of chastity, eventually sending their three living children to boarding school. She later founded a religious order and sought joy in the midst of her very broken life. Then Pierce reappeared and demanded that she return to him. When Cornelia refused, he sued her for conjugal rights; after losing on appeal, Pierce kidnapped Cornelia’s children and turned them against her and the Church. She was ultimately reconciled with only one. Asked once why she wasn’t miserable, Cornelia replied with a smile, “Ah, my child, the tears are always running down the back of my nose.” Cornelia grieved her suffering deeply but chose to live in the joy of the risen Christ.

Servant of God Rose Hawthorne Lathrop (1851-1926) was a New York socialite (the daughter of American novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne) who suffered from postpartum depression and psychosis after the birth of her only son. She received treatment and recovered, but after the death of her child a few years later, her husband’s alcoholism became so extreme that the couple separated only a few years after they had converted to Catholicism. Rose began to nurse the poor, living in the slums so she could be close to those who were dying of cancer. After her estranged husband’s early death, Rose founded a Dominican order of nursing Sisters that continues to serve and house terminally ill people living in poverty today.

Servant of God Blandina Segale (1850-1941) was an Italian-American immigrant who is known as “the fastest nun in the West.” Blandina grew up in Cincinnati, where her family moved after immigrating to the United States when Blandina was four. After high school, Blandina became a religious Sister and was soon sent to the Wild West, traveling the Santa Fe Trail to Colorado and later New Mexico where she taught public school, talked down mobs of armed vigilantes and befriended Billy the Kid. After 20 years, she headed back east where she continued to serve in unexpected ways, particularly with immigrants, incarcerated people and victims of human trafficking. After another 40 years of tireless work, Sr. Blandina retired at 83.

Servant of God Leonard LaRue (1914-2001) was an American Merchant Marine serving during the Korean War when he was sent to Hungnam in what is now North Korea. There he saw tens of thousands of Korean civilians trying to escape the advancing Chinese army. Though LaRue’s ship was designed for only 12 passengers, he dumped all his cargo and weapons into the sea and loaded 14,000 Korean refugees onto the ship. They were unarmed, with no food, little water, no medical care and no translator, but LaRue packed these people shoulder to shoulder to evacuate as many as possible. It took them two days to sail 450 miles (during which time five women on the ship gave birth), but he brought them all to safety in what’s been called “the greatest rescue by a single ship in the annals of the sea.” The descendants of those refugees number one million, including the former president of South Korea, Moon Jae-in. LaRue left the sea behind to become a simple Benedictine monk in New Jersey, where he lived in obscurity for many decades despite being a national hero on the other side of the world.

Servant of God Ida Peterfy (1922-2000) was a Hungarian girl who helped several Jewish families escape from the Nazis, dumped her boyfriend because he was an antisemite, then founded a religious order that performed subversively Catholic puppet shows in communist Hungary despite the suspicions of the communist secret police. Eventually, she fled the country escaping to Canada before ultimately settling in the United States in 1956. She lived in Los Angeles where she and her Sisters developed a style of evangelization that she called “the joyful apostolate.” Sr. Ida loved hiking and camping, so her evangelical method included Christian summer camps as well as children’s television shows that were reminiscent of her early puppet shows.

Ven. Alphonse Gallegos (1931-1991) was a Mexican-American bishop, a visually impaired priest and a product of Los Angeles public schools. He was a pastor who walked through the barrio in order to love his people better and an activist who fought abortion, racism, nuclear proliferation and unjust treatment of workers. He was a friend of César Chávez and the local lowriders, a Hispanic man who learned Spanish as an adult, a profoundly faithful priest with a grin and a cowboy hat. Known as the “bishop of the barrio” and the “lowrider bishop,” Gallegos had a resume a mile long, but the most memorable thing about him to those who knew him was his powerful, personal love for each of them. Gallegos was a bishop, yes, but he was a father first and stands as a model of priestly and episcopal holiness for all clerics who want to love their people well.