When Pope Francis made his historic visit to Iraq this past March, it placed a spotlight on a distinct group that certainly is not used to it.

Chaldeans — Catholics from northern Iraq who are in union with the Pope yet form a distinct local Church in the United States, headquartered in Southfield — are one of the oldest Christian communities on earth. They trace their lineage back to the apostle Thomas and many still can speak Aramaic, the language of Jesus.

The largest contingent of Chaldeans living outside of their ancestral homeland happens to reside in the Metro Detroit area. Often overshadowed by our region’s large Middle Eastern community, the local Iraqi Catholic population has increased from a couple dozen immigrants to more than 200,000 people in less than 100 years.

What conditions enabled such incredible demographic growth?

Beyond the economic opportunities afforded by a booming Motor City, the Chaldean community in southeastern Michigan was nourished in the 20th century by two fundamental factors: the sacrificial love of family and friends and the generous support of the local Church.

Today’s Detroit-area Chaldeans are the descendants of Babylonian farmers who harvested crops along the Tigris River more than 5,000 years ago in what is now northern Iraq. In those days, much of the region’s residents were polytheistic, believing in many pagan gods.

Following the death and resurrection of Jesus, Chaldean tradition has it that St. Thomas the Apostle evangelized northern Babylon, along with two other early disciples, St. Addai and St. Mari. Many Chaldean villages converted to Christianity by the end of the first century due to their efforts.

Fast forward to the early 1900s: Some Chaldean men were being lured away from their ancestral homeland by the prospects of making significant money in America and ultimately bringing it back to Iraq to share with their families.

Mary Romaya, a retired high school history teacher and former executive director of the Chaldean Cultural Center in West Bloomfield Township, explained that the rise of the Ford Motor Company played a large role in bringing them to Detroit.

“News of the $5 a day wage reached our villages in Iraq and Henry Ford’s advertisements on Ellis Island brought Chaldeans here,” Romaya noted. Reports of Lebanese and Syrian immigrants doing well in the Motor City’s booming industrial landscape provided further hope to Iraqi Catholics considering the move to America.

Immigrating to the United States was difficult for the first 20-25 Chaldean “pioneers” in the early 20th century. The journey began by traveling more than 500 miles from the Nineveh Plain of Iraq, sometimes by foot, to Beirut, Lebanon. There immigrants boarded steamships at the port heading west across the Mediterranean Sea. After picking up more passengers at Marseille, France, these massive boats charted a weeklong course through the Straits of Gibraltar, into the rocky waters of the Atlantic Ocean and ultimately concluding on America’s eastern seaboard.

While some were successfully admitted into the country at Ellis Island or Boston harbor, others were denied entry due to medical concerns or documentation issues. Nonetheless, these pioneers were not deterred from making it into America. Most of these Motor City Chaldean pioneers were men, hoping to make some quick cash in a few years and return home to their families with greater financial security. While a few worked in the region’s automotive factories, more decided to work for local grocery shops owned by Lebanese and Syrian families. The grocery industry was a natural fit for Chaldean immigrants, whose farming backgrounds made them familiar with fresh produce and foodstuffs. Moreover, their Middle Eastern employers could communicate with them in Arabic, enabling them to quickly learn how grocery stores were operated in America.

These new immigrants also discovered a welcoming place to practice their Catholic faith. This proved an imperative attraction of the United States later in the 19th century as well, as religious conflict and the persecution of Christians grew more rampant throughout the Middle East. During Iraqi-Kurdish conflicts in the middle of the century — some of which lasted even up until the late 1970s — churches were destroyed and entire Catholic villages were decimated. The Chaldean population in northern Iraq decreased 80 percent during these conflicts; since 2003, more than two-thirds of remaining Iraqi Christians have been displaced.

The United States — and the Motor City — became a place where Chaldeans could openly practice their faith, despite the fact there was not yet a Chaldean-rite Church in the region. The first Chaldeans in Detroit worshipped with a predominantly Middle Eastern Catholic congregation on the east side of the city: St. Maron’s Catholic Church. Built in 1916, St. Maron’s was home to hundreds of Syrian and Lebanese Maronite Catholics, and by all accounts, these newcomers from Iraq were fully embraced as part of the parish’s faith community.

Soon, these Chaldean trailblazers realized they could firmly establish themselves in the grocery business, and, more importantly, Chaldean men knew their Catholic families could be spiritually fed in Detroit.

Yalda Antoun Saroki, Mary Romaya’s father, immigrated to Detroit from Iraq in May of 1929, just a few months before the Great Depression paralyzed the country. Romaya recalls her dad’s often repeated saying when speaking of the economic hardships of the 1930s: “It was tough, but we made a living.” In spite of the downturn, Chaldeans kept on coming, often with the financial support of other Chaldeans.

Customers of early 20th century Chaldean grocery shops could easily see the deep Catholic roots and strong family bonds that permeated their culture. Often behind the counter were images of the Sacred Heart of Jesus or the Holy Family. Brothers co-owned stores and frequently brought their wives to work with them. Chaldean kids could be found stocking shelves, working on homework and eating dinner in the storage room. Romaya fondly remembers going to the Eastern Market when she was at most 6 years old. “He would haggle with local farmers for bushels of vegetables and fruit in the early morning hours and then put up by the time the store opened at 9 a.m.”

The Detroit Chaldean population continued to grow in the 1930s and 1940s. With fairly restrictive immigration quotas in place and World War II preventing many from making the journey, a different factor was responsible for the steady increase. Chaldean couples were raising large families, demonstrating their openness to God’s plan for their marital love. And as their families continued to grow with each newborn, Chaldeans made up a significant portion of the baptisms, first Communions, marriages and other sacraments taking place at St. Maron’s.

According to Romaya, Chaldeans were fully welcomed by their Catholic counterparts, regardless of race, in the early decades of the 20th century. “There was never an issue. Chaldean children, such as myself, were in Detroit Catholic schools along with other Catholic students and we were treated like everyone else. We often went to archdiocesan churches for Sunday Mass … We often attended Mass at Blessed Sacrament Cathedral, which is where I started elementary school.”

Nonetheless, in the late 1940s, the Chaldean community felt it was time for their own priest and church in Detroit. In 1947, Father Toma Bidawid answered their prayers when he arrived as the first Chaldean Rite pastor. Soon thereafter, with the support of the Archbishop Edward Mooney, Mother of God Church was completed on Hamilton Avenue in the historic Boston-Edison Neighborhood. Situated just a couple of blocks from Most Blessed Sacrament Cathedral, the Archdiocese of Detroit contributed $25,000 towards its construction. Cardinal Mooney emphasized to the Chaldean congregation the importance of the parishioners funding their new parish in its early years.

The Chaldean community, especially its women, came up with creative ways to support their new Church. While their kids played on the playground at Palmer Park, mothers got together to pray the rosary, play rummy and take up collections for the support of their priest and parish. On St. Joseph’s feast day, Chaldean women — particularly those with husbands named Joe — would also sell bread after Mass and donate all their funds raised to the Church.

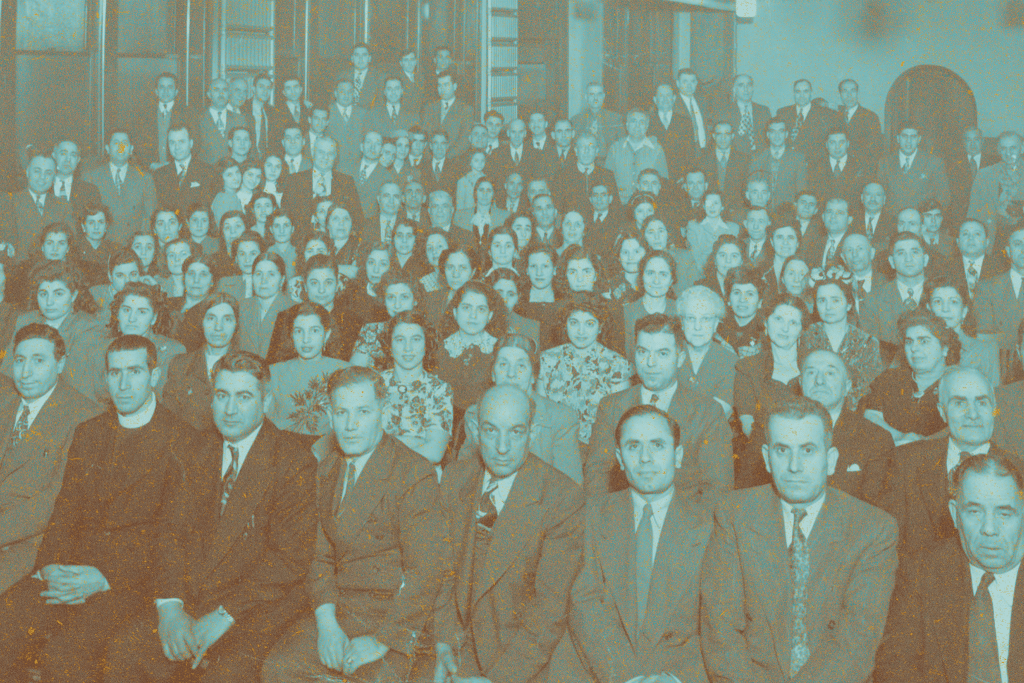

For a 20-year period starting in the mid-1940s, the Chaldean community grew significantly as a result of the increasing threat to Christianity present in Iraq. In 1943, the population of Iraqi Catholics living in Detroit was just a little more than 900. By 1963, it had more than tripled, with 3,000 Motor City Chaldean residents. Then in 1965, with the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Acts, thousands of relatives rejoined their families in Southeast Michigan over the next few decades. Chaldean households were often jam-packed during this time as they took in their uncles, aunts, cousins and extended family as they worked to become financially independent.

Ultimately, many Chaldean families established themselves in the suburbs and their mother parish, Mother of God Catholic Church, Our Lady of Chaldeans, moved to Southfield in 1980. Today, it is a cathedral and seat for the Eparchy of St. Thomas the Apostle of Detroit, covering the eastern half of the United States for the Chaldean Rite.

The conflicts the Chaldean community faces, however, continue — even in Michigan. The contingent who sought religious asylum in the United States finds themselves at odds with immigration officials as a result of travel bans and tense international relationships; in 2017, almost 10 percent of Chaldeans in Michigan were detained by ICE. These individuals knew that deportation meant imminent physical danger if sent back to Iraq.

Despite these recent changes, the Chaldean community of Metro Detroit remains rooted in the fundamental elements that make up their unique identity: a fervent Catholic faith and strong family bonds.

Chaldeans continue to grow up in multi-generational homes, where it is not uncommon for grandparents to teach their grandchildren the faith and important prayers, sometimes in Aramaic. These children, in turn, make up an outsized portion of students attending Catholic schools in Metro Detroit. The largest events in the local Chaldean community still are oriented around the reception of Catholic sacraments, with massive gatherings to celebrate baptisms, first Communions and weddings. Young Chaldean men discerning a possible vocation to the priesthood typically attend Sacred Heart Seminary, where they take theology classes alongside the archdiocese’s seminarians and learn their ancient ancestors’ language, Aramaic, at a deeper level.

In just a matter of a century, people thousands of miles away from their native country have made themselves a home away from home in Southeast Michigan.

Mary Romaya is not surprised: “You can take the Chaldean out of the village, but their Catholic faith and family will come with them. And that’s all that matters.”